When night falls across coral reefs, the ocean does not simply go to sleep. Instead, an entirely different set of behaviors unfolds beneath the surface. While some predators become more active, many reef fish must find creative ways to survive the darkness. Among the most fascinating solutions are fish that make mucus cocoons while sleeping, a strategy that sounds strange but works brilliantly.

These mucous cocoons are not random slime blankets. They are carefully crafted structures that serve as protection, camouflage, and, at times, an alarm system. In reef environments filled with nocturnal predators like moray eels and sharks, sleep is risky business.

Fish that fail to defend themselves during rest may never wake up. From hiding in rocks and sand to wrapping their whole fish bodies in a jelly-like bubble, each species balances survival with its daily energy budget.

Let’s explore the fish species that use mucus cocoons, mucus layers, or mucus-based strategies during sleep, and uncover their astonishingly diverse behavioural adaptations.

Fish That Produce Mucus Cocoons While Sleeping

1. Stoplight Parrotfish

As the sun sets over the reef, the stoplight parrotfish begins one of the ocean’s most remarkable bedtime routines. Instead of wedging itself deep into coral, this parrotfish wraps itself in a transparent mucus cocoon, forming a delicate jelly-like bubble that surrounds its body.

This mucus cocoon plays a crucial role in masking olfactory cues. Nocturnal predators such as moray eels rely heavily on smell to find fish sleeping in reef crevices. By wrapping itself in mucus, the parrotfish effectively hides its scent, making it harder for predators to see the fish in the dark.

In reefs where moray eels regularly attack fish at night, this masking can mean the difference between life and death. The cocoon also acts as protection against parasites, especially gnathiid isopods. These blood-feeding crustaceans regularly bombard fish while they sleep, latching onto exposed parts of their bodies.

Studies have shown that gnathiid isopods attack far fewer fish that produce cocoons nightly compared to those that do not. In this way, the mucus cocoon works like an underwater mosquito net, helping deter parasites and prevent infestation.

Interestingly, cocoon production is energetically costly. A parrotfish may spend up to an hour producing its cocoon using large, highly specialized glands associated with the gill cavity. Yet despite the energy cost, many parrotfish species, including the queen parrotfish and bullethead parrotfish, repeat this process every night. The payoff is a safer, more restful sleep in a reef full of danger.

2. Cleaner Wrasse

Cleaner wrasses are famous for their daytime jobs, picking parasites off larger fish, but their nighttime routine is just as intriguing. Unlike many wrasses that bury themselves in sand, the cleaner wrasse rests on the reef and forms a mucus layer over its body while sleeping. While not always a complete cocoon, this mucus bubble provides a physical or chemical barrier during bedtime.

Life on coral reefs exposes cleaner wrasse to constant parasite pressure. During the day, they remove parasitic isopods and gnathiid infestations from other fish. At night, however, they become vulnerable themselves.

Gnathiid isopods strike sleeping fish with surprising efficiency, feeding on blood and weakening infected individuals. The mucus layer helps deter parasites when the fish is relaxing and less able to defend itself.

Research suggests this behavior is part of a broader anti-parasite strategy that fish use across reef ecosystems. While cleaner fish spend daylight hours seeking cleaner organisms or acting as cleaners themselves, mucus production at night adds an extra layer of protection. It is a moderately energetically efficient way to reduce parasite loads without constant movement.

Although mucus cocoons do not make cleaner wrasse completely immune, they significantly reduce attacks. This highlights that many coral reef fishes rely on multiple strategies rather than a single perfect solution.

3. Giant Moray Eel

At first glance, the giant moray eel seems like the villain in this story rather than part of it. They are powerful nocturnal predators that hunt by scent, sliding through reef crevices with frightening precision. They are precisely the reason many fish evolved mucus cocoons in the first place.

Fishbase mentions that they use olfactory cues to locate sleeping fish hidden among coral and rocks. When a parrotfish wraps itself in a mucus cocoon, it disrupts those cues, masking the smell that would otherwise guide the eel straight to its prey. This makes cocooned fish far less detectable, even when they are only a short distance away.

Interestingly, they highlight just how effective mucus cocoons are. In areas like the Great Barrier Reef and the Indo-Pacific, reefs with abundant parrotfish show lower success rates for nocturnal predators targeting cocooned individuals. The cocoon acts as both camouflage and an early warning system, as a disturbed bubble can alert the fish to danger.

In this way, the giant moray eel indirectly shapes reef behavior. Without predators, many of these most notable nocturnal behaviours may never have evolved. Predator pressure drives innovation, and mucus cocoons are one of the reef’s cleverest responses.

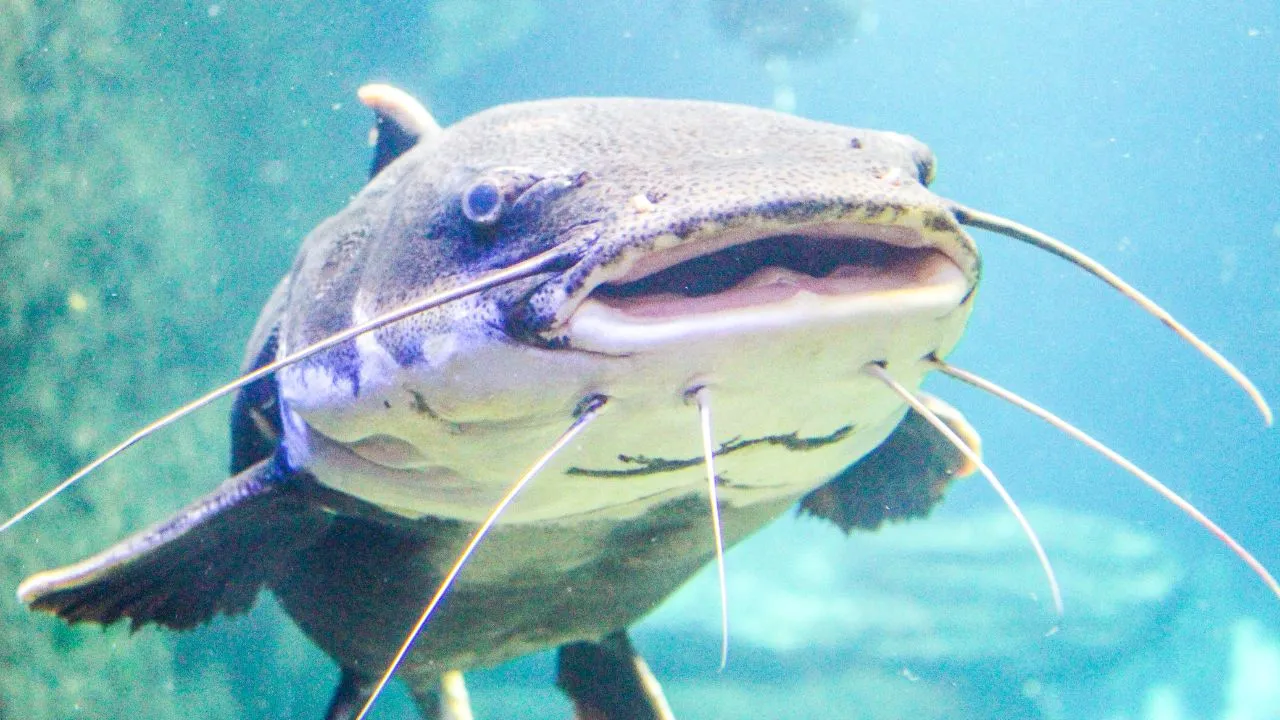

4. African Catfish

Some fish take mucus protection to an entirely different level. The West African lungfish, often mistaken for an African catfish, uses mucus not just for sleep but also for survival. When rivers dry up, this fish burrows into mud and produces a thick, hardened mucus cocoon that allows it to survive extreme conditions.

This cocoon is far more than a simple slime layer. It forms a sealed chamber that protects the fish from dehydration, predators, and infectious diseases. Inside, the fish drastically reduces activity, slowing its metabolism and surviving for years without feeding. It is a physiological adaptation that pushes the limits of what fish can endure.

Unlike reef fish that produce cocoons nightly, lungfish use cocoon production as a long-term survival strategy. The mucus even contains antimicrobial compounds, creating a chemical barrier against bacteria while the fish remains dormant. In this case, mucus is not just about sleep but about enduring harsh environments.

5. Clownfish

Clownfish do not produce whole mucus cocoons like parrotfish, but mucus still plays a vital role in how they sleep. These fish live among coral and sea anemones, organisms armed with toxic skin and venomous tentacles. Somehow, clownfish remain unharmed.

The secret lies in their mucus. Clownfish produce a specialized mucus layer that prevents anemone stings from firing. At night, when clownfish rest, often lying on their sides or wedged into coral, this mucus continues to protect them. Without it, sleep would be impossible among such dangerous hosts.

Clownfish rely heavily on their habitat for protection rather than hiding from predators. The anemone itself deters many nocturnal predators, such as sharks. In return, the clownfish feed the anemone and defend it from other fish. This mutual relationship allows clownfish to get a good night’s snooze.

Although they do not form large mucous cocoons, clownfish demonstrate that mucus can function in different ways. Whether as a protective coating or a whole bubble, mucus remains central to survival during sleep.

6. Damselfish

Damselfish are common reef fish that often rest close to coral or rocks at night. While they do not produce whole mucus cocoons like parrotfish, mucus still plays a supporting role in their nighttime survival. Many damselfish rely on mucus layers combined with strategic hiding spots.

These fish often settle into small crevices or hover just above coral, reducing exposure to predators. Their mucus provides antibacterial protection and may help minimize parasite attachment during sleep. While not as dramatic as a cocoon, it is still part of their nightly defense system.

Damselfish highlight how many fish combine behaviors rather than rely on a single solution. Hiding, mucus production, and reduced movement all work together to lower risk. In busy reef habitats, flexibility is key.

Even without producing cocoons, damselfish remind us that mucus is nearly universal among fish and plays a quiet but critical role in nighttime survival.

7. Siamese Fighting Fish

Siamese fighting fish, or bettas, take a different approach entirely. PetMD says these freshwater fish do not create sleeping cocoons. Instead, their relationship with mucus appears during reproduction rather than sleep.

Male bettas use mucus to create bubble nests at the water’s surface. The mucus stabilizes the bubbles, allowing eggs to remain protected and oxygenated. While this behavior does not occur during sleep, it shows another fascinating use of mucus in fish biology.

At night, bettas rest quietly, often near the surface or among plants. Their survival does not depend on hiding from nocturnal predators like reef fish do. As a result, mucus cocoon production is unnecessary.

Including bettas in this discussion highlights how mucus use varies widely across species. Not all fish need cocoons, but nearly all use mucus in some critical way.

Conclusion

From coral reefs to muddy riverbeds, mucus plays a surprisingly influential role in fish survival. Fish that produce mucus cocoons while snoozing reveal just how creative evolution can be when faced with predators, parasites, and harsh environments.

Whether it is a parrotfish wrapping itself in a jelly-like bubble, a wrasse forming a protective layer, or a lungfish sealing itself away for years, these behaviors show that sleep in the wild is anything but passive. Rest requires planning, protection, and often a little slime.

In reefs filled with nocturnal predators, mucus cocoons act as camouflage, parasite control, and early warning systems all at once. They help fish survive the night and wake ready to feed, clean, and maintain the delicate balance of coral ecosystems.

Next time you think of mucus as something unpleasant, remember this: for many fish, mucus is the difference between waking up and becoming someone else’s midnight snack.