While most people think of snakes as warm, lowland dwellers, some species have boldly defied expectations. These cold-tolerant, altitude-loving serpents have mastered survival in places where oxygen is scarce, temperatures plummet, and food can be hard to find.

From the high plateaus of the Himalayas to Andean slopes shrouded in fog, these snakes have adapted unique strategies to thrive in extreme conditions. Their secret? Specialized metabolisms, clever hunting techniques, and the ability to withstand cold that would leave most reptiles frozen in place.

Not only do they survive—they flourish, blending seamlessly into rugged terrains and rocky crags where few predators dare to follow. Join us on a journey into the rarified air of the world’s highest snake habitats.

Whether you’re a herpetology enthusiast, a thrill-seeking adventurer, or simply someone fascinated by nature’s quirks, these extraordinary serpents prove that life can flourish even in the most unexpected places.

Fun Fact: Did you know some snakes can thrive at elevations above 14,000 feet—where oxygen is thin and temperatures plummet? The Himalayan pit viper is one of nature’s true high-altitude survivors!

Snakes That Can Live in the Highest Altitudes

1. Himalayan Pit Viper

When it comes to altitude, most of us start gasping around 3,000 meters. But snakes? Well, some are basically mountaineers in scales. Enter the Himalayan Pit Viper (Gloydius himalayanus), a true high-altitude hero of the snake world.

Found slithering along the southern slopes of the Himalayas—from Pakistan through northern India and into Nepal—this viper is not your average garden-variety snake. Reports suggest it can climb (well, not literally climb, but slither really high) to a staggering 4,900 meters above sea level.

That’s higher than most ski resorts and certainly higher than your neighborhood jogger would dare. According to Wikipedia, this makes it the highest-living snake ever recorded. Take that, mountain goats!

This snake isn’t picky about hiding spots. It loves to tuck itself under fallen timber, slip into rocky crevices, or lounge beneath boulders and leaves. Basically, it’s the ultimate introvert, always finding the perfect hideout while keeping an eye out for lunch—likely small rodents or birds unlucky enough to wander by.

Despite its lofty lifestyle, the Himalayan Pit Viper is the only pit viper in Pakistan, which is pretty impressive. And though some reports suggest it might live in Sikkim, India, researchers are still waiting for an RSVP confirmation before adding that to its resume.

What’s truly fascinating is how this snake thrives where oxygen is thin and temperatures drop dramatically. It’s basically a cold-weather snake ninja, showing that even in the harshest, chilliest environments, life—sometimes scaly and fanged—finds a way.

Fun Fact: Himalayan Pit Vipers give live birth instead of laying eggs! That’s right—while most snakes prefer to drop off a clutch and slither away, these snakes keep their babies cozy inside until they’re ready to face the high-altitude world.

2. Andean Milk Snake

These highland adventurers live in the Andes Mountains, comfortably hanging out at elevations up to 2,700 meters (around 9,000 feet)—that’s basically VIP seating in the sky for a snake.

Unlike their lowland cousins, Andean Milk Snakes are chill masters. Literally. They can tolerate much lower temperatures than most snakes, making them the perfect example of “adapted to the cold.” But don’t worry—they’re not completely frozen in place.

These snakes spend much of their time tucked away in burrows, under logs, rocks, or fallen leaves, staying cozy, safe from predators, and avoiding the worst of the chill. It’s basically a snake version of a comfy mountain cabin retreat.

When the afternoon or evening rolls around, these sneaky hunters slither out to search for dinner. Small rodents, lizards, and sometimes insects become their unsuspecting meals. And while they’re out hunting, you can admire just how stylish these snakes are—the Andean Milk Snake’s patterns are like nature’s own high-altitude fashion statement.

Fun Fact: Despite their name, Andean Milk Snakes don’t drink milk (sorry, dairy lovers!). Their name comes from an old myth that they snuck into cow barns and “milked” the cows. In reality, they’re more interested in mice than moo juice.

3. Mexican Dusky Rattlesnake

Meet the Mexican Dusky Rattlesnake (Crotalus triseriatus), a snake that proves rattlers aren’t just sun-loving desert dwellers—they can also handle mountain life. Found in the highlands of Mexico, these snakes enjoy elevations ranging roughly from 2,000 to 3,500 meters (6,500–11,500 feet).

That’s high enough to make hikers wheeze while the rattlesnake casually slithers by, completely unfazed. True to rattlesnake form, the Mexican Dusky Rattlesnake has its own version of a “warning system”—a rattle at the end of its tail.

But don’t worry, it’s more of a polite “hey, back off” than a full-on concert. It prefers forests, rocky slopes, and areas with plenty of cover, where it can hide from predators and ambush its prey like a patient, scaly ninja.

This snake is mostly nocturnal, coming out in the cooler evening hours to hunt rodents, birds, and occasionally lizards. During the day, it retreats to shaded crevices or burrows, avoiding the harsh sun and keeping its cool—literally.

So if you’re trekking the highlands of Mexico and hear a faint rattle, take a moment to appreciate the mountain-dwelling, stealthy, and surprisingly polite Mexican Dusky Rattlesnake.

Fun Fact: Despite the intimidating rattle, Mexican Dusky Rattlesnakes are generally shy and will avoid humans if they can. Think of them as the introverted hikers of the rattlesnake world—quiet, cautious, and only making noise when absolutely necessary.

4. Eastern Brown Snakes

Meet the Eastern Brown Snake (Pseudonaja textilis), a true Australian powerhouse and one of the most venomous snakes in the world. Don’t worry, though—these snakes are generally shy, and encounters with humans are thankfully rare. Still, if you see one, it’s best not to test your sprinting skills against it.

As per the Australian Museum, Eastern Brown Snakes live in arid regions of Australia, including Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia, and Victoria, and even stretch into southern New Guinea.

But don’t let the dry, farm-friendly environment fool you—they’re also high-altitude survivors, able to thrive in places where temperatures can be cooler and oxygen a bit thinner. Basically, they’re the ultimate versatile snake, comfortable in farmlands, open plains, or higher elevations.

These snakes are fast—like, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it fast. Combine that with venom that ranks among the most potent in the world, and you have a predator that commands respect without trying too hard.

Most of the time, though, Eastern Brown Snakes are more about quietly hunting rodents and small mammals than causing chaos for humans.

Fun Fact: Despite their fearsome reputation, Eastern Brown Snakes are quite shy and avoid confrontation. You could think of them as introverted sprinters: incredibly capable, high-powered, but mostly minding their own business unless provoked.

5. European Adder

Say hello to the European Adder (Vipera berus), also known as the black adder—Europe’s most common venomous snake and quite possibly its most cold-tolerant reptile. This stocky little survivor has mastered the art of living where most snakes would pack it up and move south.

In fact, in the northern reaches of its range, it’s often the only snake species brave enough to stick around. The European Adder has one of the widest ranges of any snake, stretching from Great Britain across Europe and deep into Asia, all the way to northern China.

It reaches as far north as Scandinavia and holds a truly impressive title: the only snake known to live above the Arctic Circle. Yes—this snake basically laughs in the face of frost.

Cold doesn’t scare the adder, but it does make it sleepy. These snakes can hibernate for up to nine months a year, which honestly sounds like a dream. Even more impressively, some young adders are born while their mother is still hibernating—talk about making an entrance without waiting for spring!

European Adders are mostly ground-dwelling hunters, feeding on small mammals and ground-nesting birds. They’re usually active during the day, but in warmer southern regions, they may switch to nighttime activity to avoid the heat.

You’re most likely to spot one along woodland edges, in open countryside, or occasionally climbing small banks or bushes to bask in the sun like a reptile enjoying a rare spa day.

Fun Fact: The dark coloration of black adders isn’t just for looks—it helps them absorb heat more efficiently, making them better suited for cold climates. It’s basically nature’s version of wearing black in winter.

6. Himalayan Keelback

Meet the Himalayan Keelback (Herpetoreas platyceps), a sleek and adaptable grass snake that proves not all high-altitude snakes need venom to survive. Belonging to the Colubridae family, this species is endemic to South Asia, meaning it’s a true local—no international travel required.

The Himalayan Keelback is right at home in the cool, mountainous regions of the Himalayas, where it thrives in forests, grassy slopes, and areas close to streams or wetlands. Unlike its more dramatic venomous neighbors, this snake relies on agility, camouflage, and quick reflexes to get by.

Keelbacks are often found slithering through grass, basking on rocks, or hiding under logs and stones to escape the cold. Their keeled (ridged) scales give them a rough texture, which helps with grip—perfect for navigating uneven terrain in high-altitude environments.

While it may not have the fame of vipers or rattlesnakes, the Himalayan Keelback plays an important role in its ecosystem, keeping populations of frogs and small prey in check.

Fun Fact: The Himalayan Keelback is an excellent swimmer and is often spotted near water, making it one of the few mountain snakes that’s just as comfortable in streams as it is on land.

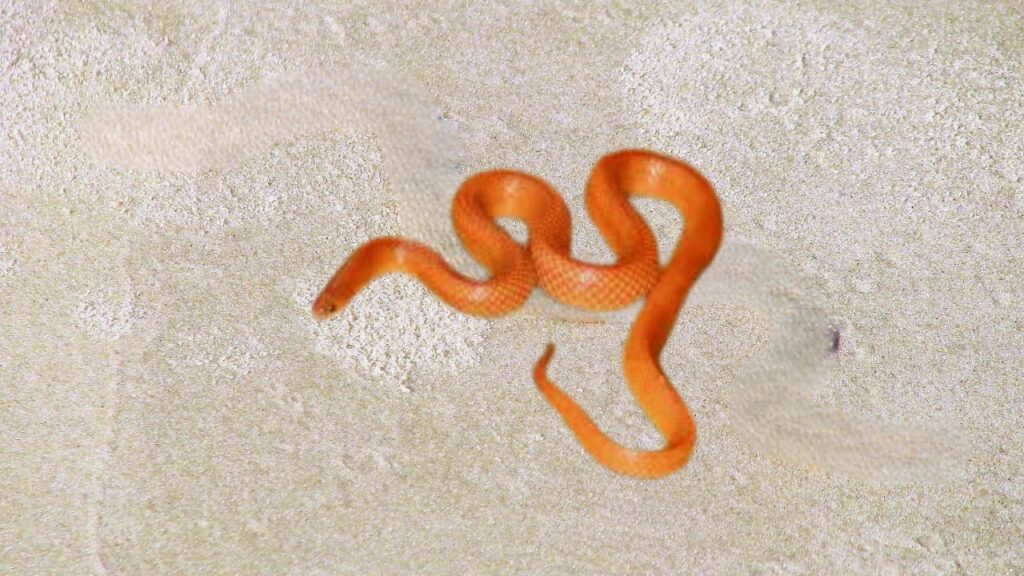

7. Red Coral Kukri Snake

Don’t let its small size fool you—the Red Coral Kukri Snake (Oligodon species) is one of the most fascinating little snakes you’ll ever meet. Named after the kukri, a curved knife from South Asia, this snake gets its dramatic name from its razor-sharp, knife-like teeth.

Native to parts of South and Southeast Asia, the Red Coral Kukri Snake is often found in forested regions, grassy areas, and sometimes higher elevations, where it skillfully adapts to cooler and more variable climates.

It’s non-venomous, but what it lacks in venom, it makes up for in clever design and attitude. These snakes are mostly ground-dwellers, spending their time hidden under leaf litter, rocks, or logs. They’re secretive and shy, preferring to avoid attention—until dinner time.

Their specialty? Eggs. Those knife-like teeth are perfect for slicing open reptile eggs, allowing them to enjoy a meal most snakes can’t easily access. Talk about a niche skill set.

Fun Fact: When threatened, the Red Coral Kukri Snake may flatten its body and flash its bright red or coral coloring as a warning. It’s basically saying, “I’m small, but I’m dramatic—back off.”

Conclusion

Some asian pit vipers and other high-altitude snakes found across North America’s ranges, northern Mexico, the Himalayan region, and parts of Colorado demonstrate surprising resilience in harsh habitat conditions. Living in the wild, these animals rely on sharp sense abilities to avoid predators, locate food, and survive cold, snow-covered environments that would challenge most reptiles.

For a person camping in these central mountain areas, encounters may come as a surprise, reinforcing the need to be careful despite lingering doubt that snakes can live so high. Ongoing research continues to build hope and understanding of how these snakes adapt, proving that life at extreme elevations is possible even for cold-sensitive reptiles.